By Vidya Rajan, Columnist, The Times

It’s migration season. The males have left, and I expect that the females will leave soon too. Flying geese honk overhead, the plethora of robins pecking in the garden have moved on, and the birdseed in the feeders lasts much longer with the insatiable starlings gone. With the big task of seasonal travel underway or looming for these and other animals, I will look at some of the animals that migrate seasonally, and then return in a future article to the mechanisms.

It’s migration season. The males have left, and I expect that the females will leave soon too. Flying geese honk overhead, the plethora of robins pecking in the garden have moved on, and the birdseed in the feeders lasts much longer with the insatiable starlings gone. With the big task of seasonal travel underway or looming for these and other animals, I will look at some of the animals that migrate seasonally, and then return in a future article to the mechanisms.

Knowledge of the migratory abilities of animals has been of longstanding interest. Migration is primarily thought to be a movement between breeding and non-breeding grounds, but evidence shows that this is not the case for all animals.[1] The Renaissance was a time of questioning, and migration was one of those unknowns queried. Entertainingly the explanations for the disappearance of animals during parts of the year and their reappearance triggered some truly astonishing hypotheses. In 1555, Swedish fishermen in supposedly pulled up swallows along with fish (baffling, but they probably misunderstood Pliny’s comment in the 1st century about hirundo or sea-swallows, a type of fish), and experimentalists even tested the hypothesis by tossing swallow birds into water (where they immediately went into permanent hibernation, aka death), or by providing them with water, reeds and mud, which they shunned.[2] The truth was revealed when a ring placed on a swallow chick in England was recovered in South Africa. Also swallows that arrived during the British summer were thought by medieval Europeans to burrow underground in the winter – apparently in 1785, farm workers digging out a foxhole found “bushels of swallows in torpid condition”. We are now in possession of more data which do not support the existence of burrows with hibernating swallows.

Animals migrate through the air, on land, and in water. All migrations are seasonal and follow weather patterns which set up food abundances that chase through the airscape, landscape or waterscape.

Land migrations have been recorded since time immemorial. Predators and hunter-gatherers followed migrating animals herbivores through their feeding grounds, which followed weather patterns, following rains which caused parched ground to erupt new vegetation. The Serengeti is home to some of the greatest animal migrations ever recorded. Andersen and colleagues used data collected on the ground between 1999 and 2020 to describe the movement of rains which then set up successive waves of migrants – first zebras, then wildebeest, then gazelles including the forage and the contents of the stomachs.[3] Historically, the great plains of North America were home to the bison migrating in staggering numbers, churning up dust clouds from horizon to horizon. Records of bison herds with millions of animals in 1806 shrank to very few in the 1850s. because of the double whammy of 15,000 to 25,000 bison being shot and killed annually[4] (see a photograph of a pile of bison skulls waiting to be ground to fertilizer), but also because of a historic drought. Caribou, pronghorn, bighorn sheep and elk are among the large-hoofed animals that migrate in the US (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Migrations paths of animals across the North American continent compiled from tracking organizations. From: https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2023/01/protecting-migratory-corridors-bottled-wildlife

Aquatic migrations are less remarked upon, but no less remarkable, than land migrations. There are two types of aquatic migrations: vertical and horizontal. The reasons for the “Diel vertical migrations” include protection from UV, searching for colder water and predator evasion; ironically, predators chase them anyway, and also migrate vertically. For instance, microscopic animal-like zooplankton (200mm in length) move up and down the ocean up to distances of 3,000 feet every day (this is about 500,000,000 body lengths – the equivalent of a 6-foot-tall human traveling to the moon and back every day.) They are followed by fish that eat the zooplankton, which are followed by larger predators, like Humbolt squids. At night, zooplankton move to the ocean surface to feed on their prey, photosynthetic phytoplankton.

In horizontal aquatic migrations, humpback, grey and blue whales migrate for birthing in southern waters and then travel to cold, forage-rich polar waters for feeding; leatherback and loggerhead turtles feed in colder waters, but also breed in warmer waters – sometimes on beaches where they themselves were born – but their migrations may be maturity related rather than seasonal. Phytoplankton need sunlight and are present close to the surface, and can get swept along on seasonal ocean surface currents. They are chased in turn by crustaceans like krill and fish like sardines, which become food for larger animals, from birds to fish to mammals like whales, elephant seals, walruses, dolphins and porpoises. The Greatest Shoal on Earth is the nickname given to the movement of millions of newly spawned sardines near Africa’s Cape Agulhas which move up the east coast along with a seasonal upwelling of cool water, which traps them against warmer waters of the Indian Ocean which their physiology cannot tolerate. Trapped in this unsuitable habitat, they become prey to a feeding frenzy by fish, mammals and birds. The reasons that these sardines migrate this path is thought to be a geo-evolutionary phenomenon – the Indian Ocean was a cool sardine nursery during the glacial periods. But this migration will slow and stop as waters continue warming with climate change, and the upwelling of cool water that the sardines move in, to their doom, also disappears.[5]

Aerial migrations are the ones that decidedly capture the imagination. In addition to flying birds and bats, insects like locusts, dragonflies and butterflies migrate.[6] Satterfield et. al. (2020) estimate that 2-5 trillion insects undertake long-range seasonal migrations.[7] Some migrate for reproduction (salt marsh mosquitoes), are irruptive (unpredictable, like painted Lady butterflies which move with El Nino weather patterns) or nomadic (locusts which go from solitary individuals to forming swarms of billions of insects).[8] Among seasonal migrants, fragile, colorful Monarch butterflies migrate across the length of North America (Figure 2) to rendezvous in a small region in California or Mexico, even though they have never been there (and their great-great-grandparents left there the previous year). In the spring, the migrating survivors move back north over two or three short-lived generations during the summer, to eventually colonize their great grandparents’ birthplaces and lay eggs. These eggs hatch into the overwintering Monarchs which retrace their own great-great-grandparents’ journey in the Fall.[9] The longest insect migration is that of the wandering glider dragonfly, which annually travels about 10,500 miles across the Indian Ocean from East Africa to India.

Figure 2: Long-lived overwintering Monarchs initiate spring migrations. Multiple short-lived summer generations eventually arrive at the northernmost boundaries and lay eggs (left panel). The eggs hatch into long-lived fall offspring which migrate south and initiate the following spring movement northwards (right panel). From: https://monarchwatch.org/migration/

Mexican freetail bats and the lesser long-nose bat are unusual (among bats) in migrating seasonally. Both types of bats migrate from the southwestern states to northern areas following food availability. According to the US National Park Service, many types of bats are pollinators which consume agave nectar, but the plant is becoming less abundant due to urbanization and agave flower harvesting for tequila, and the bats are now threatened and endangered.[10] Many types of bats stay put through the winter, going into hibernation[11] but they are having problems too. An infection called “white-nose syndrome” (WNS) is killing hibernating bats. The fungus’ name is Pseudogymnoascus destructans (sharing a specific name similar to Varroa destructor); you can imagine the devastating effects it is having on populations.

But the champions of aerial migrations are birds, both by distance traveled and in number. The birds that travel furthest are the tiny Arctic terns (1 foot long, weighing about 4 oz), which seeks the arctic and austral summer, traversing the entire longitudinal distance from pole to pole twice a year, a distance of 44,000 miles, or 15 times the distance between Los Angeles and New York City. They are thought to follow the magnetic lines of force each way, but this does not explain their ability to land in the same place each year even though the magnetic pole shifts over considerable distances in unpredictable fashion. Hummingbirds have been recorded as living for as long as 9 years, traveling to the warmer south in the northern hemispheric winter and heading the other way as the weather warms. A horde of other birds migrate: geese, hawks, and songbirds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 protects migrating birds in the United States, making it “unlawful to hunt, take, capture, kill or sell” migrating birds. Eggs, nests, dead birds and dead bird parts are also protected.

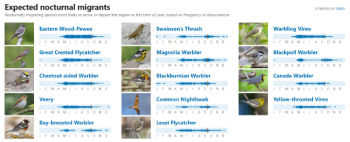

The Pennsylvania migratory birds website at https://dashboard.birdcast.info/region/US-PA gives insight into how many birds pass along this flyway at night across our state (Figure 3). Because they fly at night, light disorients them; please turn off bright outdoor lights so they can use the natural light of the stars and moon as they have for millennia.

Figure 3: Nocturnal migrants flying south across Pennsylvania. From: https://dashboard.birdcast.info/region/US-PA

As little songbirds migrate through some areas like Singapore, parts of China or Cyprus, they are caught in large numbers and eaten. In Cyprus, the practice is notionally illegal,[12] but restaurants cook the birds as a delicacy – 2 million were killed in 2015, of which 78 were already threatened species. Of course, the impacts on populations of the already debilitating travel are devastating. In 2024, the numbers killed were 435,000.[13] Like the sardines of the Greatest ShoaI, these birds have been using this path for millions of years, and cannot suddenly swerve to avoid poachers.

Cooked migrating songbirds is a dish that will probably stick in many throats.

[1]. Dingle, H. (2006). Animal migration: is there a common migratory syndrome? Journal of Ornithology, [online] 147(2), pp.212–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-005-0052-2

[2]. Britain, S. (2022). The mysterious case of the disappearing swallows. [online] Bite Sized Britain – Britain’s amazing history and culture. Available at: https://www.bitesizedbritain.co.uk/however-we-have-not-always-known-where-swallows-go111

[3]. T. Michael Anderson, Hepler, S.A., Holdo, R.M., Donaldson, J.E., Erhardt, R.J., Hopcraft, G.C., Hutchinson, M.C., Huebner, S.E., Morrison, T.A., Muday, J., Munuo, I.N., Palmer, M.S., Johan Pansu, Pringle, R.M., Sketch, R. and Packer, C. (2024). Interplay of competition and facilitation in grazing succession by migrant Serengeti herbivores. Science, 383(6684), pp.782–788. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg0744. Also see associated e-letter from me regarding an alternative interpretation of the data which includes the presence of latex-producing forbs which cannot be digested by monogastric zebras, but are exposed for polygastric wildebeest and gazelle foraging).

[4]. National Park Service (2021). What Happened to the Bison? (U.S. National Park Service). [online] www.nps.gov. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/what-happened-to-the-bison.htm

[5]. Eurasia Review (2021). World-Famous Sardine Migration Explained By Genomics. [online] Eurasia Review. Available at: https://www.eurasiareview.com/16092021-world-famous-sardine-migration-explained-by-genomics/

[6]. Texasento.net. (2025). Migratory Insects of North America. [online] Available at: https://www.texasento.net/migration.htm

[7]. Satterfield, D.A., Sillett, T.S., Chapman, J.W., Altizer, S. and Marra, P.P. (2020). Seasonal insect migrations: massive, influential, and overlooked. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(6), pp.335–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2217

[8]. ThoughtCo. (n.d.). Why Do Insects Migrate? [online] Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/insect-migration-1968156

[9]. monarchwatch.org. (n.d.). Monarch Migration. [online] Available at: https://monarchwatch.org/migration/

[10]. Nps.gov. (2017). Night Flyers: Desert Pollinator Bats – Pollinators (U.S. National Park Service). [online] Available at: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/pollinators/migratingbats.htm

[11]. www.nps.gov. (n.d.). Hibernate or Migrate – Bats (U.S. National Park Service). [online] Available at: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/bats/hibernate-or-migrate.htm.

[12]. Bhattacharya, S. (2016). Scientific American. [online] Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/slaughter-of-the-song-birds/ [Accessed 25 Sep. 2025].

[13]. Rspb.org.uk. (2024). Rise in wildlife crime in Cyprus. [online] Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/whats-happening/news/cyprus-bird-trapping